Over the past year or so, I’ve come across the occasional remark or comment about InfoSec teams and phishing simulations; typically how they’re run extremely poorly.

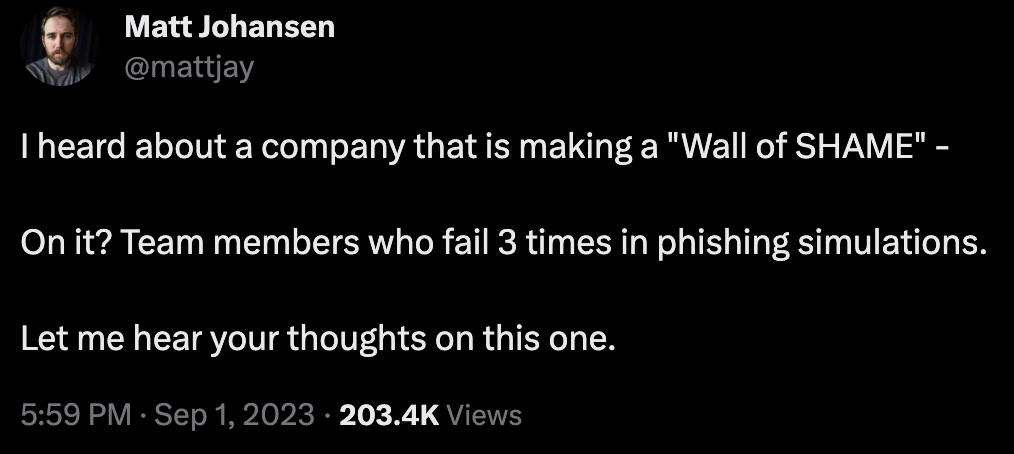

Most recently I came across this thread on Twitter and thought I would share my thoughts on phishing simulations and the effectiveness of them; based on my own experiences and understanding. My opinions could change as more data becomes available on the topic.

Ignorance is bliss, or not

Once upon a time, I used to painstakingly handcraft beautifully designed phishing simulations. The end to end process of designing, sending and analysing the results used to take about 3-4 hours (it would probably take half the time now with the help of ChatGPT).

There was a strange sensation, almost a thrill immediately after sending out these simulations. My eyes were glued to the screen as I stared at real-time updates. The numbers on the admin dashboard climbed rapidly as people opened emails, clicked links, and submitted their credentials.

As time went on, the company grew as did my responsibilities so it was no longer feasible for me to spend hours hand cranking these simulations so we did what you do and outsourced the task of creating phishing simulations to a vendor to automate it for us.

The question is, were these endeavours effective? And even more pressing, were they the right kind of effective?

What’s wrong with phishing simulations?

Many organisations fall into a trap with phishing simulations. They use them to criticise colleagues or entire departments, simply because they clicked on a link in an email.

I have also observed that many organisations capture and report metrics on the simple act of clicking a link (this is called the “click-through” rate).

In other words, the industry has done so poorly at security that employees are deemed to have “failed” and shamed for simply using their devices as intended.

It’s also worth noting that almost every simulation I have seen only taught people how to spot simulations; it wouldn’t actually improve people’s ability to spot the real signs of a phish.

Lastly, by making the rest of the organisation feel as if they’re under constant testing, a natural resistance and barrier emerge between InfoSec and everyone else. While I could elaborate on the psychological elements at play, I hope it’s apparent that fostering a culture of ‘us versus them’ fails to create a safe, thriving environment

The Illusion of Effectiveness: Why Phishing Simulation Metrics Mislead Us

If your “click-through” rate (a terrible metric in my opinion – if we’re going to report on anything, it should be the act of actually submitting your credentials) is 99%, what will you do? Run more awareness campaigns? Buy more tools from vendors? Or, God forbid, create a wall of shame making people feel bad for simply trying to get their work done?

Similarly, what if that number were 1%? Would you celebrate, claiming you’ve done an amazing job, while naively ignoring the reality that anyone can be phished by a semi-determined threat actor?

In one of my previous engagements, I was assigned the task of getting access to the configuration file of a sensitive, well known security vendor. I sent one phish. One email to a senior member of the security team. They responded to the email with the configuration file attached; mission success.

I say this to beat the drum to the fact that everyone can and will be phished at some point and that no-one is immune, not even your security team.

What should we be focusing on?

Instead of spending tens or hundreds of thousands (did someone say millions?) on ineffective security controls and questionable and irrelevant security awareness platforms, prioritise the things that will actually make a difference. Focus on phishing resistant authentication such as WebAuthn and Passkeys. Make sure every app you can get is behind your SSO platform.

In my last two engagements at Mettle Bank and Algbra; both UK FinTechs, I rolled out phishing resistant authentication (we called it strong user authentication). In both companies, the security culture was so strong that the rollouts were smooth and seamless. For example, at Mettle Bank, the CEO was one of the first people to volunteer during the rollout.

In the security world, it’s rare that you come across solutions that provide both a significant boost in user experience and security; this is one of them.

What will I be doing going forwards?

At the beginning I mentioned how I used to personally run my own phishing simulations and how I then outsourced that to a security vendor.

Although the graphs were interesting to analyse, they showed that people became more engaged and collaborative when we shifted our focus from testing to real security awareness programmes. Over time, the allure of ‘free Subway voucher’ emails fades, and herd immunity begins to erode as people start tuning out the noise.

So, what would I do differently now?

Rolling out phishing resistant authentication across the entire user base has become a mandatory requirement for me. As I mentioned previously, it significantly boosts the user experience (Google have a whitepaper which goes into more detail on the UX point) and security by effectively eliminating phishing threats.

Secondly, I strongly believe in the effectiveness of continuous security awareness.

Sending people links to off-the-shelf training platforms where you’re forced to watch a video for an hour about content that is 95% irrelevant to the way the company operates, doesn’t work. Testing people doesn’t work. We’ve all been sent mandatory learning slides and videos and we’ve all clicked “next, next, finish” given the first opportunity.

Sure, you might have a 100% completion rate across your organisation but did anyone take anything away from it?

This is one of the reasons why I prefer to give face-to-face (whether in person or over Zoom) sessions with new joiners as I’ve found it to be significantly more effective and engaging. You don’t build a thriving security culture by someone droning on about password complexity requirements on a pre-recorded video.

Lastly, would I encourage the use of phishing simulations? Their effectiveness is questionable and I don’t think they provide enough actionable value for it to be worth it.